Although we had a little help with things that required specialty tools such as the water jet cutting and the laser engraving these knives are hand made from start to finish by myself and my bride to be.

This is the process we undertook in order to create them.

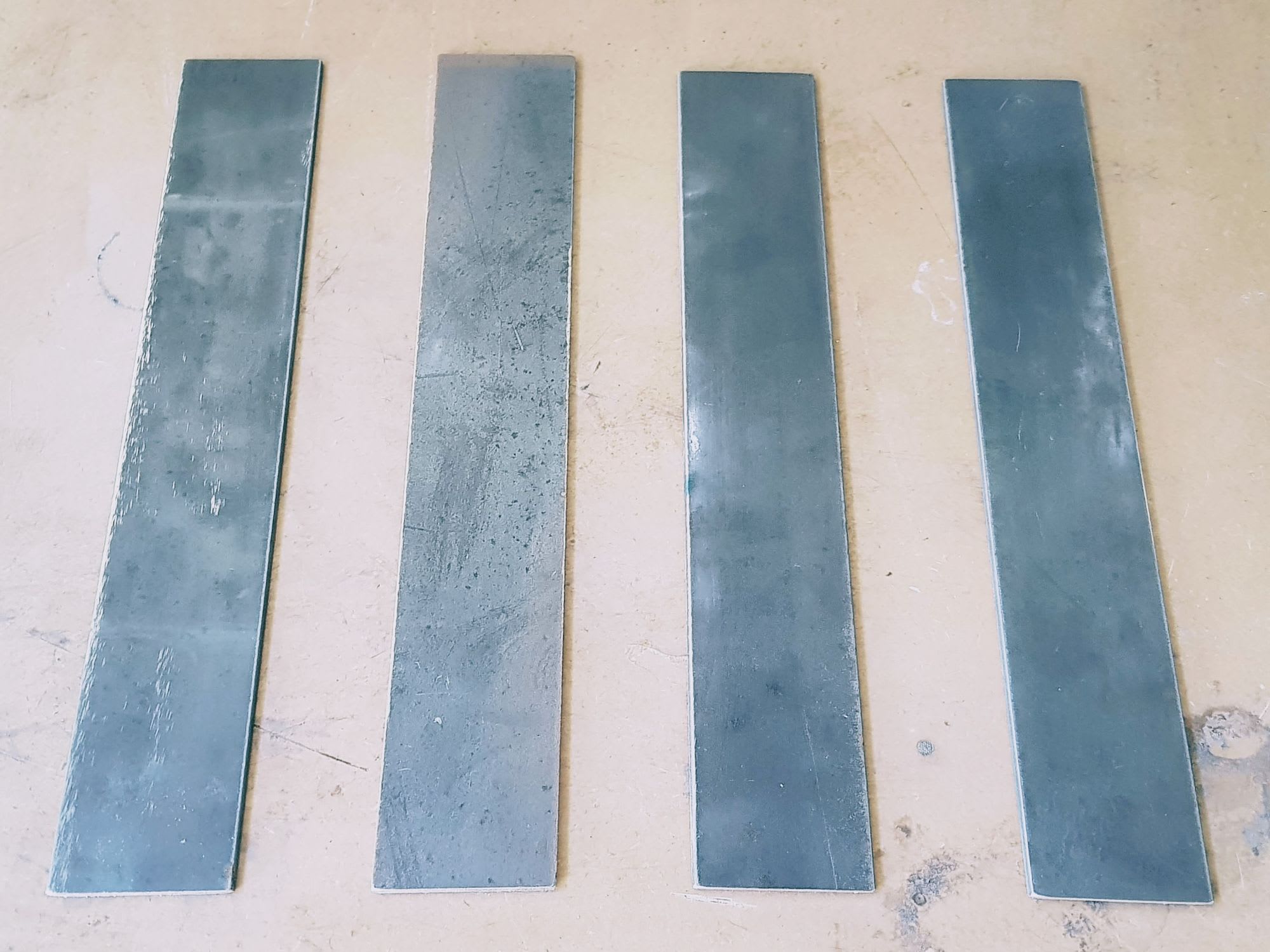

Knives are brought into this world as steel, rolled out into flat bars which are then cut into the rough shape of the knife using high pressure water jet cutter - imagine a pressure washer on steroids.

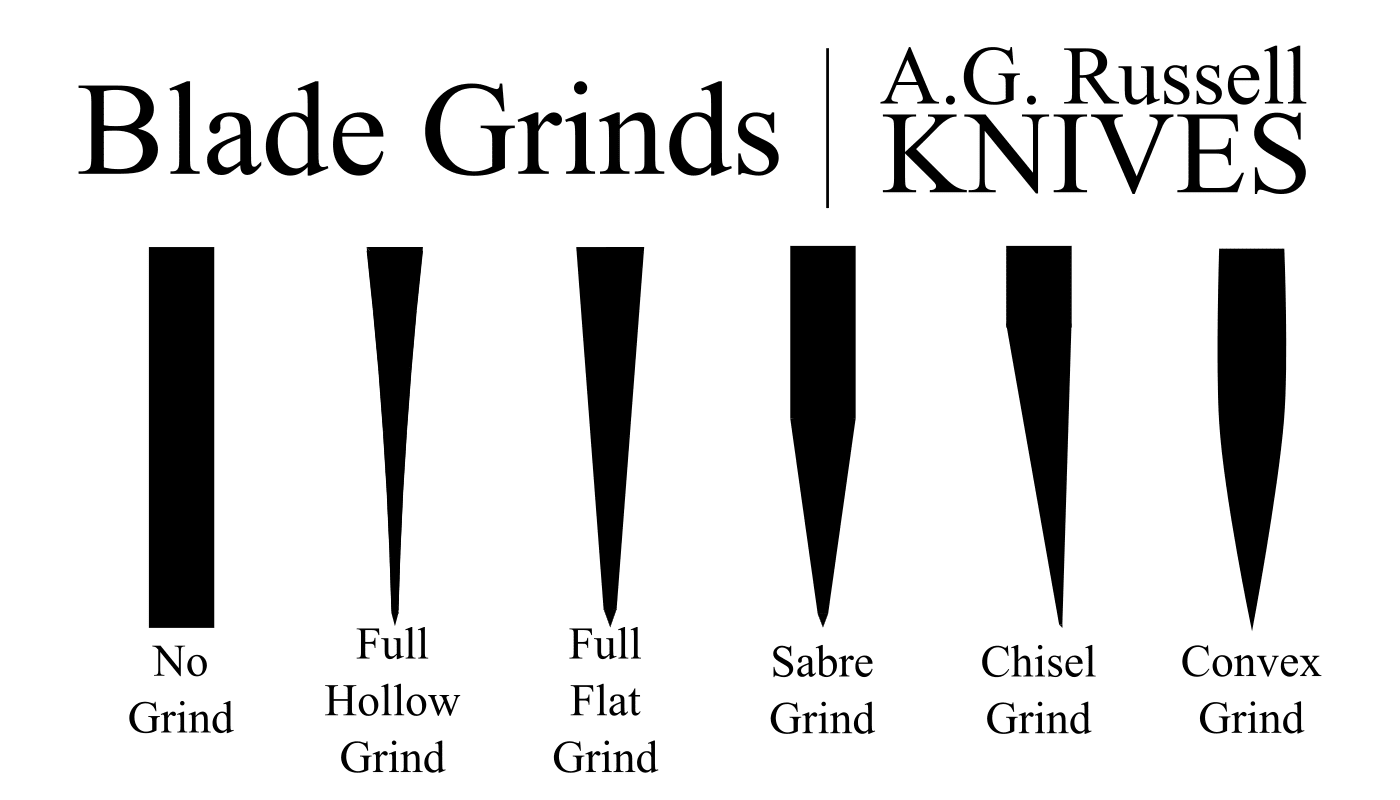

The edges on these knives are ground in the style of a full flat grind, which is thickest at the spine for strength, but tapers down into a relatively thin edge for excellent slicing.

A full flat grind is often stronger than a hollow grind, and will cut better than a sabre grind.

Once the grinding is completed, sanding starts at 80 grit and progresses to 180 grit in preparation for heat treating. Doing a little work now saves about two hours per knife later on.

From here each blade is heated up to non-magnetic temperatures and allowed to cool down naturally.

This is performed twice before having clay slathered all over the blade to allow for differentially hardening and to produce a rather fetching hamon - the difference between hard and soft steel.

Once the clay has dried the blades are once again heated up to a non-magnetic temperature - about 900°c - and quenched in warm oil.

The blades in this state are incredibly fragile and if they were dropped they would shatter.

To counter this the blades are throw into an oven and tempered at 200 degrees for 2 hours.

When everything has cooled down the knives are ground again, this time to a closer finish and hand sanded, starting from 80 grit sandpaper and progressing through grits 120, 180, 220, 400 to finally end up at 600 grit.

The last step is finishing them with varying grades of a scotchbrite like material.

The handles are made out of wood and made in pairs;

- Two handles made from red river gum that was slightly eaten by termites with gaps filled with resin and black dye, bolsters made from jarrah.

- Two are made from African mahogany with gidgee bolsters.

- The last two handles are ancient bog oak, donated by one of the groomsmen, the gaps filled with resin and a purple pearlescent dye and bolsters made from jarrah.

Holes are drilled down the middle of the handle to a length of 120mm, whereas the bolster has the shape carved out by hand using two of my grandfathers chisels.

To test the fit of everything the knife is inserted into the bolster and handle. If it looks good to go the wood is glued together temporarily using CA glue.

When the CA glue has cured, the handle is sanded down into a hexagonal shape with the butt and bolster getting slightly rounded on the tips.

Sanding is done progressively from 80 grit to 600 grit, the handle is then given a sizable dosage of food grade mineral oil and beeswax to seal the wood.

Given a few days for the oil to seep into the wood, it gets a quick polish using a sisal buffing wheel.

Each knife is now glued in to the handle securely using a two part epoxy which is left to cure in an upright position for 3 days to achieve maximum bond strength.

Using varying grades of diamond hones and a leather strop, the blade eventually come to a razor sharp edge.

Finally everything is given a once over, any blemishes polished out using a microfibre cloth and cleaned up with a thin layer of food grade mineral oil and packaged, ready for the big day.